What is Health?

Which would you say?

- Health is feeling good.

- Health is having lots of energy.

- Health is the absence of disease.

- Health is being active.

- Health is eating right.

- Health is staying hydrated.

- Health is looking good.

- Health is getting proper rest.

These are some of the most common answers and may be some of the answers you may give as well. The truth is, many of these answers are correct and some are misguided. We’re going to analyze some of the misguided ideas of health.

How many people do you know look and feel good but have high blood pressure, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, etc.? We have been influenced to think that health comes down to how we feel and look. The fitness industry piggy backs on this idea and markets based on this delusional philosophy.

If health is just about how you look and feel, then why do some of the fittest individuals in the health industry suffer heart attacks?

We have been programmed to think that the healthiest people in the world are the ones on health and fitness magazines, athletes, health gurus, marathon runners, popular social media figures that personify this image of health and the list goes on.

There is a place for looking and feeling great in health, however, it is not the way we ought to measure whether someone is healthy or not. The question above about a random heart attack should leave you questioning this dogmatic idea about health.

Health is not about the absence of disease either. We all know that we are mortal and that our bodies will eventually atrophy to the point of death. Many health fanatics use this idea as a way to market their authority on being experts on health advice, but they fail to acknowledge that death comes upon us all. The language of not being sick, being free from disease, looking and feeling great is the language they use to persuade you to listen to them. This kind of language misses the mark when it comes to real health, however, many people are led to believe this type of philosophy of health.

For many of us, we are constantly trying to find the perfect formula for health, so when you hear someone speak this way, it is easy to lend an ear and mimic their lifestyle in your own life hoping for the same results. Unfortunately, this is wishful thinking and it still may not be the answer to avoid getting sick for the rest of your life.

To be fair, there are ways to reduce the amount of times you get sick and build disease in the body, however, to think that we can find a way to be 100% preventative is a lost cause.

The statement about having energy, eating well, staying hydrated, staying active, and getting proper rest are closer to the idea of what is health. Yet, they still do not get to an adequate microbiological, anatomical, chemical, and physiological definition of health. These are lifestyle practices that enhance our health and support proper bodily function but are not the cause of how the body functions well or not.

The Definition of Health

“Health is when all the cells in the body are functioning and healing at 100% and is not simply when someone is void of any disease, illness or pain.”

The list of lifestyle practices listed earlier are the result of your body functioning and healing as close to 100% as possible. There is something that precedes all these lifestyle practices that enables them to have beneficial health effects.

You may ask and think, “What possibly could precede staying hydrated, eating healthy food, staying active, and getting proper rest? These are the lifestyle practices that allow the body to be healthy!”

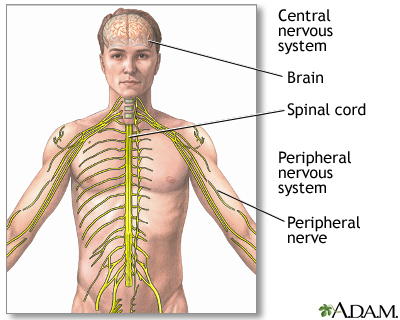

Whether you want to believe it or not, it is your “Central Nervous System” (CNS) that enables the body to reap the benefits of the healthy lifestyle practices above.

Your Central Nervous System consists of your brain, spinal cord, and nerves and is the first system to form in the human embryo. Every biological, physiological, chemical, and cellular function in the body is controlled by your CNS.

You know that we can go a long time without food, days without water but we cannot survive a second without proper nerve supply to the body. If you cut the nerve supply in your body, then it is lights out for any bodily function.

The CNS is what causes your body to function and heal at 100% every day. While toxins, poor nutrition, lack of activity, poor hydration, not enough sleep and many others are a part of all disease process’, the begin stages of disease starts when the CNS is not functioning at 100%. Sub-optimal CNS function leads to poor biological, physiological and chemical function in your body. As a result, your body begins to build disease in the body over the course of time.

There is a clear connection between your viscera (organs) and their relationship to your spinal cord, nerves and brain. The health of your organs depends on the level of proper nervous system function. The better it is, the better your organs function and drive away disease daily. The poorer your CNS is, the faster your organs shut down and create disease.

There was a study done at the University of Pennsylvania by Dr. Henry Winsor showing that the condition of your spine to maintain healthy CNS function is pivotal at maintaining a healthy body.

In the study, Dr. Winsor dissected animal and human cadavers to see if there was a relationship between the diseased organs and the vertebrae and nerves that went to those organs. He did find that there was a relationship between diseased organs and poor curvatures in the spine that lead to organ shut down, poor function and disease.

The Connection

The first 7 vertebrae of the spine make up your “neck” or “cervical spine” (C-1 through C-7).

C1 Blood supply to the head, pituitary gland, scalp, bones of the face, brain, inner and middle ear, sympathetic nervous system.

C2 Eyes, optic nerves, auditory nerves, sinuses, mastoid bones, tongue, forehead.

C3 Cheeks, outer ear, face bones, teeth, tri-facial nerve.

C4 Nose, lips, mouth, Eustachian tube.

C5 Vocal cords, neck glands, pharynx.

C6 Neck muscles, shoulders, tonsils.

C7 Thyroid gland, bursae in the shoulders, elbows.

The next 12 vertebrae of the spine make up your “middle back” or “thoracic spine” (T1-T12).

T1 Arms from the elbows down, including hands, wrists, and fingers; esophagus and trachea.

T2 Heart, including its valves and covering; coronary arteries.

T3 Lungs, bronchial tubes, pleura, chest, breast.

T4 Gall bladder, common duct.

T5 Liver, solar plexus, circulation (general).

T6 Stomach.

T7 Pancreas, duodenum.

T8 Spleen.

T9 Adrenal and supra-renal glands.

T10 Kidneys.

T11 Kidneys and uterus.

T12 Small intestines and lymph circulation.

The next set of 5 vertebrae make up your “low back” or “lumbar spine” (L1-L5).

L1 Large intestines and inaugural rings.

L2 Appendix, abdomen and upper leg.

L3 Sex organs, uterus, bladder and knees.

L4 Prostate gland, muscles of of the lower back and sciatic nerves.

L5 Lower legs, ankles and feet.

The last two areas of the spine are the “sacrum” and coccyx”

Sacrum Hip bones and Buttocks.

Coccyx Rectum and Anus.

Now that you see the relationship between the CNS and your organs, what types of spinal conditions cause your CNS to breakdown leading to organ disease and death?

Any interference to the CNS caused by improper spinal alignment is called, “subluxation.” It is the condition of “subluxation” that leads the CNS to breakdown.

What is "Subluxation?"

“A vertebrae subluxation is a minor or major misalignment of a vertebrae or several vertebrae. These misalignments, some that are so small that they need to be measured with an instrument, invade spinal space, put pressure on the spinal cord, compress nerves and/or push soft tissue out of the way and into delicate neurological tissue” (Cruise Ship or Nursing Home p. 86 (see bibliography).

When a subluxation occurs by improper spinal alignment, then the body functions at suboptimal levels causing organ breakdown and disease.

What are some causes of subluxation?

- Birth process

- Poor posture whether it is sitting or standing.

- Chemical exposure in environment, foods, drinks, medications, etc.

- Physical, mental or emotional trauma.

- Improper lifting of heavy objects.

- Athletics of all types

Subluxation of the spine are occurrences that happen from birth and extend to the rest of our lives. Many of us are symptom free for many years before we experience poor function, numbness, pain, headaches, muscle tension, organ failure, etc.

The thought of having our spines looked at comes after we have been experiencing some of these symptoms for some time. The truth is, when we have subluxations of the spine, the body is shutting down well before any symptoms come to the surface. Years, if not, decades go by before the symptoms come to the surface.

Subluxation of the spine are occurrences that happen from birth and extend to the rest of our lives. Many of us are symptom free for many years before we experience poor function, numbness, pain, headaches, muscle tension, organ failure, etc.

The thought of having our spines looked at comes after we have been experiencing some of these symptoms for some time. The truth is, when we have subluxations of the spine, the body is shutting down well before any symptoms come to the surface. Years, if not, decades go by before the symptoms come to the surface.

There are numerous ways to check the spine for “subluxations:”

- Posture

- X-rays

- EMG (electromyography)

- Thermography

- Range of Motion

- Muscle Strength Evaluations

Subluxation of the spine is not the language used to diagnose improper spinal alignment in the medical field, so you may be diagnosed with scoliosis, degenerative disc disease, sciatica, herniated discs, arthritis in the spine, etc., by an allopathic medical doctor, specialist, radiologist, surgeon or neurologist. These are just conditions caused by cumulative subluxations listed above. They are the symptoms and not the cause.

The typical treatments offered for these conditions by the medical field are:

- Surgery

- Pain Medication

- Physical Therapy and/or massage therapy

Depending on the situation, these methods may be necessary, however, they do not fix the underlying condition of subluxation. None of the classifications of physicians just mentioned are qualified to correct the problem of subluxation. This may sound harsh to say, however, the curriculum and methods of treatment these doctors learn in medical school are not designed to fix the underlying problem of subluxation.

So what kind of doctor is qualified to fix subluxations of the spine?

You may have guessed it, “A Chiropractor!”

Many people are scared to death to go to a chiropractor. The main reasons come from “myths” or “false ideas” that people and medical professionals have regarding chiropractors.

Myth #1 - Fear of having your neck broken

Many of us have seen in movies where someone grabs someone’s head and neck and twists it really fast and the next thing you know the person is dead. The images from movies have given us a lasting impression that this is how you break your neck and can die.

Based on this image and idea, people are very reluctant to go see a chiropractor because they think they do something similar to the head and neck. Unless there is tons of force applied to the head and neck area, it is impossible for anyone to die this way or having their neck broken. The amount of pressure applied to the upper neck (cervical spine) during an adjustment is not even close to causing this result.

In fact, the noise you hear when your neck gets adjusted is just air being released from the joints in the neck. Sometimes when you get adjusted, you do not even hear what seems to be a popping noise.

The chiropractic adjustment is designed to create more space between vertebrae, releasing spinal compression on your discs and reduce the amount of pressure being applied to your nerves in the spinal cord. An adjustment helps the brain and spinal nerves send signals back and forth more efficiently for proper organ function. The adjustment is literally “turning your power on” so the body can function and heal closer to 100%.

Their job is to correct the “subluxation” that many of us have and eliminate the interference so that our “central nervous system” can function properly. That is what a “chiropractic adjustment” is and not “cracking” your back.

All physicians get some form of malpractice insurance that costs 100’s of thousands of dollars depending on what they practice. Chiropractors spend an average of $1500 a year on malpractice insurance because it is so safe. Look up the average cost of malpractice insurance for doctors and you will see that chiropractors spend a lot less than regular allopathic physicians.

Myth #2 Chiropractors just want your money and multiple visits

Why is chiropractic care not a one minute or one adjustment fix?

If you go back to the “causes of subluxation” earlier in this article, you will see that our spines have been going through the process of degeneration since birth. What is scary is that the spine has to be about 80% broken (subluxated) before any symptoms come to the surface. So the body breaks down over many years before people experience pain, numbness, organ malfunction, etc.

When you get your spinal x-rays and go over the results with a chiropractor, you will see for yourself this slow degenerative process by the condition of your spine. This is not based on opinion or belief but on empirical science and the x-rays reveal that to you. Obviously, some people are worse than others but most of us have spinal subluxations at some level. If so, then your body is not functioning at 100%.

So when someone bends over and their back goes out and they slip a disc, it is because their spine has had some form of subluxation for many years, whether it be scoliosis, degenerative disc disease, etc., and the pressure on the spinal nerves and the inflamed discs between vertebrae finally give out.

Unless you experience extreme force to the spine that may cause issues like scoliosis, ruptured discs, twisting of the spine, etc., symptoms are caused by years of abuse and are not isolated events.

To put chiropractic care into perspective there are three main phases that you will go through when you go to a chiropractor’s office and the cost is reasonable compared to crises care, surgery, drugs, etc, that do not fix the problem of subluxations.

Phase 1: Crisis Care

In phase 1, the number of visits you will have is typically 12 to 18 depending on the test results you get in the office. This means that for the first 4 to 6 weeks, you will get adjusted three times a week so the chiropractor can really work on those subluxations that you have had for many years.

If you think about it, that many visits after many years of spinal degeneration is nothing short of a miracle to get your body functioning and healing better.

Phase 2: Active/Corrective Care

In phase 2, you have exited the crisis care and are now reducing your visits to just two times a week. The number of visits in this phase of care ranges between 12 to 36. Your adjustments will be twice a week for the next 6 to 18 weeks in the active/corrective care stage.

This phase continues your spinal corrections from years past and corrects ongoing subluxations that occur in-between each visit.

Phase 3: Maintenance Care

In phase 3, you are reducing your visits to once a week. This third and final stage is to maintain all previous adjustments and maintains any new subluxations that occur throughout the week before your next week’s adjustment.

As you can see, it takes you 10 to 24 weeks to get you from crisis care to maintenance care. In the grand scheme of things, that is a fast turnaround from all those years of spinal degeneration to get you headed in the right direction. A direction of better function and healing and preventing surgery and the need for prescription drugs all at once.

The cost for the first year of chiropractic care ranges between hundreds to a couple thousand dollars. After the first year, the cost of care goes down because you will just go once a week for 52 weeks each year. The average cost is around $30 a visit. Keep in mind, these are average amounts and each case is different depending on the condition of everyone’s individual spinal condition and what kind of care will be required to maximize your results.

The cost for chiropractic care is a fraction of the cost of doing surgery and/or getting on pain medications to manage symptoms that do nothing to fix the problem. Following this trajectory may leave you disabled, addicted to pain medication, experience poor organ function, have chronic pain, missed workdays and the list goes on.

There is no comparison in cost between chiropractic corrective and preventative care and the traditional medical treatments of surgery or pain medication management. If you speak to those who opted for spinal surgery or pain medication, ask them if it did much of anything to fix their spinal conditions like degenerative disc disease, scoliosis, or any other form of subluxation. Then ask those who opted for chiropractic care to prevent surgery or getting on pain medication instead. The answers will vary but you will more than likely hear them speak about how chiropractic care has saved their life and the small cost is worth every penny.

You may say: “see, I told you so, this is where chiropractor’s hook you in to go to them for the rest of your life!”

Keep in mind that your spine will continue to create subluxations for the rest of your life that need to be corrected. Once you make some progress after the first year of care, to pay 30 to 45 dollars a visit each week is about the cost of a tank of gas to keep your body functioning optimally, preventing disease and allowing your body to heal itself.

Now that is cheap real health care!!! You just have to make it a priority in your life.

Myth #3 Chiropractor’s are not real Doctor’s

Chiropractor’s have been called “quacks” for a very long time by the medical profession and the general public have adopted this label as well. They are not taken seriously and are thought to be wanna be doctors. Physicians and many people think they do not get the education like physicians do in medical school. That they are lesser because they do not study enough in the areas of “pathology,” “psychiatry,” “obstetrics,” or “pharmacology.” Since they do not prescribe medication, do surgery and are not up to date on new technological medical treatments, the belief is that chiropractors are living in the stone ages with in-effective treatments.

Would it surprise you that chiropractor’s have more education hours in many subjects than allopathic doctor’s do in medical school? Let’s take a look at multiple subjects and compare hours taken by chiropractors and allopathic medical students.

Chiropractors

456

243

296

161

145

408

149

56

66

271

168

Total: 2,419

Anatomy/Embryology

Physiology

Pathology

Chem/Biochem

Microbiology

Diagnostics

Neurology

Psychology/Psychiatry

Obstetrics/Gynecology

X-Ray

Orthopedics

Medical Doctors

215

174

507

100

145

113

171

323

284

13

2

Total: 2,047

Wow! Who knew that chiropractors have longer hours of study than medical doctors! If this chart does not convince you that chiropractors are real doctors based on the same subjects of study, then the belief that they are not will outweigh the facts presented in this chart for you.

Chiropractors are real doctors and are the ones who specialize in treating your spinal conditions so that your central nervous system can functioning close to 100% every day for the rest of your life. They literally remove the “interference” created by “subluxations” so your body can function the way it was created to function. A body created full of life and energy.

Remember, a chiropractic adjustment is literally “turning your self-healing power on in your body!”

Getting a chiropractic adjustment is one of the best gifts of health you can do for yourself and your family!

Myth #4 Chiropractors are only good for neck and back pain

Many people decide to go to a chiropractor when they have exhausted many options to address their neck and back pain. Pain in the neck and back are the result of a spine that is 80% broken after years of misalignment.

The medical practice of chiropractic care was never created to address neck and back pain. Neck and back pain are the result of spinal misalignment’s; not the cause.

Chiropractic care is about removing the interference caused by subluxations so your body can function at 100%.

This article has repeated some things numerous times but you must begin to see that chiropractors who perform chiropractic adjustments and what it is designed to do debunks these myths about these wonderful doctors.

Find people who routinely go see chiropractors and let them share their stories with you and you may be surprised to hear things like:

- I was able to stop taking medications to treat my symptoms.

- I have less back and neck pain.

- My scoliosis is gone or is getting better.

- I am sleeping better.

- My learning ability and memory has improved.

- My headaches/migraines are gone or occur less.

- My allergies have gotten better.

- My digestion has improved.

- My asthma is gone or has improved.

- I have less sciatic pain.

- The numbness in my arms, legs, hands or feet are gone or have improved.

- My mobility has improved.

- I have better neurological function.

- The list goes on….

If you are really attentive and open reading this article, then the next question we need to ask ourselves is:

What kind of chiropractor should I go to?

Like any other profession, there are all types of methods used to practice medicine and the field of chiropractic is no exception.

There are numerous ways that chiropractors adjust their patients. Ironically, some chiropractors just treat symptoms of neck and back pain, are just out to adjust you, take your money, and send you on your way. Different technologies are used by chiropractors to prepare the patient for an adjustment and after the adjustment, etc.

There are all types of chiropractors out there and so you must do your homework before deciding on which chiropractor to go to.

Here is a list of things to look for in a chiropractor to help you make an informed decision on where to receive your spinal care:

- Do they have you fill out paperwork prior to your first visit to learn about your medical history and lifestyle?

- Do they provide reading material to help you better understand the questions of the “why” and “how” of their treatment methods? This helps you to see if they are about educating you and letting you know how they can help you and not just adjust you and take your money.

- Do they do a “thermal scan” and “x-rays” on your first visit to see what condition your spine is currently in before doing your first adjustment? An examination and x-rays should be done first so the chiropractor can observe your spine to see where the adjustments need to be made before your first adjustment. A chiropractor who does not look at your spine first with x-rays before adjusting you is a red flag.

- Do they have you come in for a second appointment to go over your test results to see what they found on your x-rays and tell you how they can help you? This helps them see where the spine needs to be adjusted and a time where the chiropractor tells you what is going on in your spine with visual posters, so you have an image to help you see what is going on with your spine.

- Do they have you come in for a third appointment that is sometimes called, “Doctor’s Report?” This is a time for the chiropractor to go over some general health information, go over your x-rays, your first-year care plan, answer any questions you have regarding care and insurance.

- Do they have you doing warm-up exercises to do in the office prior to getting your adjustment? This helps to loosen the muscles and ligaments and hydrates the discs to maximize your adjustment.

- Do they have you doing spinal rehab exercises after the adjustment with a weighted system to stabilize the adjustment you just had?

- Do they have you doing exercises at home with specific equipment in-between adjustments to help you maximize your results?

- Do they do follow-up exams and x-rays throughout the year as a part of your care plan? This is required to see how your spine is moving, so they can make adjustments to how they adjust you and what exercises you are doing at the office and home. If the chiropractor does not re-examine the spine a few times a year, then how will they know what kind of progress you are making?

- Do they teach you how to think better, eat healthier, exercise, minimize toxins in your lifestyle and home to increase your health, bodily function and prevent disease? In other words, do they focus on overall health education?

- Do they provide you with “payment options” each year regarding your care plan to fit your budget? Will they make adjustments to your care plan, if the first care plan or re-curing care plans do not fit your budget? There are limits to how much they can adjust your care plan but find someone who works with you as much as they can.

- In the event that you move, do they work with other doctors around the country, so they can refer you to another reliable chiropractor where you are moving to or in a town nearby? This shows you that they care about your long-term well-being and want to make sure you keep getting adjustments as part of your healthy and preventative lifestyle.

The questions just provided will give you a good lens to see what kind of chiropractor services each office provides and if many of the questions can be answered with a “yes” then you know that you are in the right place.

Another good thing to do is talking with people who go to the chiropractor you are inquiring about and get them to share their experience with you. Everyone has a different experience but testimonies go a long way, especially the good ones.

Have any questions? We’d love to help!

I have personally been getting chiropractic adjustments for many years and would love to share my experience with you and help guide you in your decision with a chiropractor.

We want to hear from you!

What did you learn from this article?

What did you like best?

What was confusing about the article?

What are you willing to do with the information provided in this article?

Have you had a bad experience with a chiropractor in the past? If so, does this article help you to see that not all chiropractors are created equal?

What are some of your concerns?

What are some stumbling blocks that may get in the way of you seeing a chiropractor?

Do you have a different perspective on chiropractors after reading this article?

Do you think chiropractors are real doctors? Even if, they do not do surgery or prescribe medications?

Please send us any questions you have at info@nutrabrandlabs.com

Bibliography

Lerner, Ben D.C., Loman, Greg, D.C., Majors, Charles, D.C., Pellow, Chris, D.C., Shuemake, Eric, D.C., Cruise Ship or Nursing Home. Orlando, FL. Maximized Living Inc., 2013.

Cramer, Gregory D., & Darby, Susan A., Basics and Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and ANS. St. Louis, MS. Mosby, Inc., 1995.

All references below come from the Cramer and Darby textbook reference above:

Isherwood, I. & Antoun, N.M. (1980). CT scanning in the assessment of lumbar spine problems. In M. Jayson (Ed.) The lumber spine and back pain (2nd ed.). London: Pitman Publishing.

Jackson, R. et al. (1989). The neuroadiographic diagnosis of lumbar herniated nucleus pulposes. II. A comparison of computed tomography (CT) myelography, CT-myelography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Spine, 14, 1362-1367.

Kricun, R., Kricun, M., & Danlinka, M. (1990). Advances in spinal imaging. Radiol Clin Am, 28, 321-339.

Kushner, D.C. & Cleveland, R. H. (1988). Digital imaging in scoliosis. In M.E. Kricun (Ed.). Imaging modalities in spinal disorders. Philadelphia, WB Saunders.

Lancourt, J.E., Glenn, W.V. & Wiltse, L.L. (1979). Multiplanar computerized tomography in the normal spine and in the diagnosis of spinal stenosis. A gross anatomic-computerized tomographic correlaiton. Spine., 4, 379-390.

Louis, R. (1985). Spinal stability as defined the three-column spine concept. Anatomia Clinica, 7, 33-42.

Mayoux-Benhamou, M.A. et al. (1989). A morphometric study of the lumbar foramen: Influence of flexion-extension movement and of isolated disc collapse. Surg Radiol Anat, 11, 97-102.

Mixter, W.J. & Barr, J.S. (1934). Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med, 211, 210-215.

Paris, S. (1983). Anatomy as related to function and pain. Symposium on Evaluation and Care of Lumbar Spine Problems. Ortho Clin North Am, 14, 476-489.

Rydevik, B. et al. (1984). Pathoanatomy and physiology of nerve root compression. Spine, 9, 7-15.

Shapiro, R. (1990). Talmudic and other concepts of the number of vertebrae in the human spine. Spine, 15, 246-247.

Shealy, C.N. (1975). Facet denervation in the management of back and sciatic pain. Clin Orthop, 115, 157-164.

Wang, A., Wesolowski, D., & Farah, J. (1988). Evaluation of posterior spinal structures by computed tomography. In J.H. Bisese (Ed.), Spine, state of the art reviews, spinal imaging: Diagnostic and Therapeutic applications. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus.

White, A.A., & Panjabi, M.M. (1990). Clinical Biomechanics of the spine (2nd ed.) Philadelphia: JB Lippincott.

Lumley, J.T. (1990). Surface anatomy: The basis of clinical examination. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston.

Oliver, J., & Middleditch, A. (1991). Functional anatomy of the spine. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Fujiwara, K. et al. (1988). Morphometry of the cervical spinal cord and its relation to pathology in cases with compression myelopathy. Spine, 13(11), 1212-1216.

Grant, R. et al. (1991). Changes in intracranial CSF volume after lumbar puncture and their relationship to post-LP headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 54, 440-442.

Morris, J.H. & Phil, D. (1989). The nervous system. In R.S. Cotran, V. Kumar, & S.L. Robbins, (Eds.). Robbins pathologic basis of disease (4th ed.). Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Schoenen, J. (1991). Clinical anatomy of the spinal cord. Neurol Clin, 9(3), 503-532.

Turnbill, I.M. (1973). Blood supply of the spinal cord: Normal and pathological considerations. Clin Neurosurg, 20, 56-84.

Bland, J. (1987). Disorders of the cervical spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Bogduk, N. (1986a). An anatomical basis for the neck-tongue syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 44, 202-208.

Bogduk, N. (1986b). The anatomy and pathophysiology of whiplash. Clin Biomech, 1, 92-101.

Bogduk, N. (1986c). Headaches and the cervical spine (editorial). Cephalalgia, 1, 7-8.

Bogduk, N., Lambert G., & Duckworth, J. (1981). The anatomy and physiology of the vertebral nerve in relation to cervical migraine. Cephalagia, 1, 11-24.

Darby, S. & Cramer, G. (1994). Pain generators and pain pathways of the head and neck. In D. Curl (Ed.), Chiropractic approach to head pain. Baltimore: William & Wilkins.

Edmeads, J. (1978). Headaches and head pain associated with diseases of the cervical spine. Med Clin North Am, 62, 533-544.

Trevor-Jones, R. (1964). Osteo-arthritis of the paravertebral joints of the second and third cervical vertebrae as a cause of occipital headaches. S Afr Med J, May, 392-394.

Van Dyke, D. & Gahagan, C. (1988). Down’s syndrome cervical spine abnormalities and problems. Clin Pediatr, 27, 415-418.

Viikari-Juntara, E. et al. (1989). Evaluation of cervical disc degeneration with ultralow field MRI and discogrophy: An experimental study on cadavers. Spine, 14, 616-619.

Alvarez, O., Roque, C.T., & Pampati, M. (1988). Multilevel thoracic disk herniations: CT and MR studies. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 12, 649-652.

Cook, S.D. et al. (1986). Upper extremity proprioception in idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop, 213, 118-123.

Deacon, P., Archer, J., & Dickson, R.A. (1987). The anatomy of spinal deformity: A biomechanical analysis. Orthopedics, 10, 897-903.

Dupuis, P.R. et al. (1985). Radiologic diagnosis of degenerative lumbar spinal instability. Spine, 10, 262-276.

Hasue, M. et al (1983). Anatomic study of the interrelation between lumbosacral nerve roots and their surrounding tissues. Spine, 8, 50-58.

Nissinen, M. et al. (1989). Trunk asymmetry and scoliosis. Acta Paediatr Scand, 78, 747-753.

Pal, G.P et al. (1988). Trajectory architecture of the trabecular bone between the body and the neural arch in human vertebrae. Anat Rec, 222, 418-425.

Paris, S. (1983). Anatomy as related to function and pain. From Symposium on Evaluation and Care of Lumbar Spine Problems. Orthop Clin North Am, 14, 476-489.

Scapinelli, R. (1989). Morphological and functional changes in the lumbar spinous processes in the elderly. Surg Radiol Anat, 11, 129-133.

Spapen, H.D. et al. (1990). The straight back syndrome. Neth J Med, 36, 29-31.

Vernon, L., Dooley, J. & Acusta, A. (1993). Upper lumbar and thoracic disc pathology: A magnetic resonance imaging analysis. J Neuro musculoskeletal System, 1, 59-63.

Wyatt, M.P. et al. (1986). Vibratory response in idiopathic scoliosis. A J Bone Joint Surg, 68, 714-718.

Arnoldi, C.C., et al. (1976). Lumbar spinal stenosis and nerve root entrapment syndromes. Clin Orthop, 115, 4-5.

Bergmann, T. F., Peterson, D. H. & Lawrence, D. J. (1993). Chiropractic Technique: Principles and Procedures. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Cassidy, J. & Kirkadly-Willis, W. (1988). Manipulation. In W. Kirkaldy-Willis (Ed.), Managing low back pain (2nd ed.). New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Cox, J. (1990). Low back pain: Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment (5th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Crock, H.V. (1981). Normal and pathological anatomy of the spinal nerve root canals. J Bone Joint Surg, 63, 487-490.

Day, M.O. (1991). Spondylolytic spondylolisthesis in an elite athlete. Chiro Sports Med, 5, 91-97.

Ericksen, M.F. (1976). Some aspects of aging in the lumbar spine. Am J Phys Antropol, 45, 575-580.

McNab, I. (1971). Negative disc exploration: An analysis of the causes of nerve-root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg, 53A, 891-903.

Olsewski, J.M. et al. (1991). Evidence from cadavers suggestive of entrapment of fifth lumbar spinal nerves by lumbosacral ligaments. Spine, 16, 336-347.

Pal, F.P. et al. (1988). Trajectory architecture of the trabecular bone between body and the neural arch in human verterbrae. Anat Rec, 222, 418-425.

Paris, S. (1983). Anatomy as related to function and pain. Symposium on Evaluation and Care of Lumbar Spine Problems, 475-489.

Adams, R.D. & Victor, M. (1991). Chronic nontraumatic diseases of the spinal cord. Neuro Clin, 9 (3), 605-623.

Brooks, V.B. (1986). The neural basis of motor control. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carpenter, M.B. (1991). Core text of neuroanatomy (4th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Davidoff, R.A. & Hackman, J.C. (1991). Aspects of spinal cord structure and reflex function. Neurol Clin, 9 (3), 533-550.

Ghez, C. (1991b). Posture. In E.R. Kandel, J.H. Schwartz, & T.M. Jessell (eds.), Principles of neural science (3rd. ed.). New York: Elsevier.

Kelly, J.P. (1991). The sense of balance. In E.R. Kandel, J.H. Schwartz, & T.M. Jessell (Eds.), Principles of neural science (3rd ed.). New York: Elsevier.

Lance, J.W. (1980). The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology, 30, 1303-1313.

Nashner, L.M. (1976). Adapting reflexes controlling the human posture. Exp Brain Res, 26, 59-72.

Weiser, B. et al. (1990). Human immunodeficiency virus type I expression in the central nervous system correlates directly with extent of disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 87, 3997-4001.

Theil, H.W., Clements, D.S. & Cassidy, J.D. (1992). Lumbar apophyseal ring fractures in adolescents. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 15, 250-254.

Twomney, L., & Taylor, J.R. (1990). Structural and mechanical disc changes with age. J Manual Med, 5, 58-61.

Abdel-Azim, M., Sullivan, M., & Yalla, S.V. (1991). Disorders of bladder function in spinal cord disease. Neurol Clin, 9(3), 727-740.

Barron, K.D. & Chokroverty, S. (1993). Anatomy of the autonomic nervous system: Brain and brainstem. In P.A. Low (Ed.) Clinical autonomic disorders. Boston: Little, Brown.

Camilleri, M. (1993). Autonomic regulation of gastrointestinal motility. In P.A. Low (Ed.), Clinical autonomic disorders. Boston: Little, Brown.

Cross, S.A. (1993a). Autonomic disorders of the pupil, ciliary body, and lacrimal apparatus. In P.A. Low (Ed.), Clinical autonomic disorders. Boston: Little, Brown.

de Groat, W.C. & Steers, W.D. (1990). Autonomic regulation of the urinary bladder sex organs. In A.D. Loewy & K.M. Spyer (Ed.), Central regulation of autonomic functions. New York: Oxford University Press.

de Groat, WC. et al. Mechanisms underlying the recovery of urinary bladder function following spinal cord injury. J Auton Nerv Syst, 30, S71-S78.

Janig, W. (1988). Integration of gut function by sympathetic reflexes. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol, 2(1), 45-62.

Sato, A. (1992b). Spinal reflex physiology. In S. Haldeman (Ed.), Principles and practice of chiropractic (2nd ed.). East Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange.

Sato, A., Sato, Y., & Schmidt, R.F. (1984). Changes in blood pressure and heart rate induced by movements of normal inflamed knee joints. Neurosci Lett, 52, 55-60.

Seftel, A.D., Oates, R.D., & Krane, R.J. (1991). Disturbed sexual function in patients with spinal cord disease. Neurol Clin, 9(3), 757-778.

Stewart, J.D. (1993). Autonomic regulation of sexual function. In P.A. Low (Ed.), Clinical autonomic disorders. Boston: Little, Brown.

Taylor, G.S. & Bywater, R.A. (1988). Intrinsic control of the gut. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol, 2(1), 1-22.

April, C., Dwyer, A., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. II. A clinical evaluation. Spine, 15(6), 458-461.

Bogduk, N. (1984). The rationale for patterns of neck and back pain, Patient Management, 13, 17-28.

Bogduk, N., Lambert, G.A., & Duckworth, J.W. (1981). The anatomy and physiology of the vertebral nerve in relation to cervical migraine, Cephalalgia, 1, 11-24.

Dwyer, A., Aprill, C., & Bogduk, N. (1990). Cervical zygapophyseal joint pain patterns. I. A study in normal volunteers, Spine, 15(6)., 453-457.

Edmeads, J. (1978). Headaches and head pains associated with diseases of the cervical spine. Med Clin North Am, 62(3), 533-544.

Baxter, J.S. (1953). Frazer’s manual of embryology. London: Bailliere., Tindall & Cox.

Beck, F., Moffat, D.B. & Davies, D.P. (1985). Human embryology (2nd ed.) Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.